What does the future of Chinese wine taste like? That was the question posed at 67 Pall Mall Singapore, where Richard Hemming, Master of Wine, led an exclusive tasting of award-winning and recommended Chinese wines, each handpicked from the Wynn Signature Chinese Wine Awards held in Macau earlier this year.

“The Chinese wine industry is at a really fascinating point in its development,” Hemming began, addressing a room filled with wine enthusiasts and members of the London-originated wine club which Hemming was an original founding member of the London club. “What started as an attempt to emulate Europe’s finest wines is now evolving into something far more individual.”

Charting a New Identity

The Wynn Signature competition, founded by Australian winemaker Eddie McDougall, is gaining international attention for its scale and ambition. Modelled after Decanter’s format, the awards were launched as part of Macau’s push to diversify its tourism sector by investing in non-gaming activities.

Created to spotlight the depth and potential of China’s domestic wines, the competition was judged by a panel of Chinese and international wine experts. “Basically, you taste each wine in silence and score it out of 100,” Hemming explained. Wines were tasted blind in small groups, and scores were compared and debated after each flight. With 900 wines entered across multiple days, the judging was rigorous, resulting in 27 trophies awarded.

Having personally tasted more than 200 entries, Hemming noted a wide spectrum in quality. Some wines, he admitted, were clearly not ready for release, with a few showing technical faults. “It made me wonder,” he said. “Are people drinking these flawed wines and thinking that’s what good wine is meant to taste like?”

Learning from the Old World, Looking to the New

In just a generation, Chinese vineyards have spread across vast territories, Ningxia, Xinjiang, Shandong, Yunnan, planted with classic European varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Syrah, and Marselan. The early instinct was to imitate Bordeaux or Burgundy, but local conditions, extreme winters, high altitudes, arid soils, and irrigation-dependent farming, are prompting winemakers to rethink their approach.

“There’s a pink line across the wine map of China,” Hemming said, pointing at a projected map. “You wouldn’t expect the wines from Xinjiang to taste the same as those from Shandong. Funnily enough, they kind of do at the moment.”

That’s because many Chinese producers are still emulating European styles, making wines to match an expected taste profile rather than letting the terroir lead. “Many producers are still figuring out what works,” Hemming explained. “That’s why it’s too soon to set rules or define appellations, they don’t want to cut off any options before knowing what they do best.”

Challenges of Price and Presentation

There are also hurdles beyond the vineyard. Pricing remains a challenge. Without the legacy of prestige that supports the high prices of Bordeaux or Burgundy, Chinese producers are left with a dilemma: price their wines according to what they think they’re worth, or compete at entry-level with better-known global brands. For now, Hemming suggested, many are caught in the middle.

Language and branding are another barrier. “If you need a translation app just to read the back label,” he said, “that’s already an obstacle for most international drinkers.”

Yet signs of progress are undeniable. Many young winemakers are returning home after studying abroad, bringing global standards with them. Domestic wine culture is shifting, too, as younger consumers grow more curious, swapping traditional spirits for something new in their glass.

“Wine bars are opening. People are starting to care about what good wine actually tastes like,” said Hemming.

A Treasure Hunt Through China’s Vineyards

The masterclass featured a standout of Chinese wines at the Macau competition, from method traditionnelle sparkling wine to bold reds made with Marselan and Syrah. Each wine reflected not just technical skill, but also regional potential, “These wines aren’t just competition winners,” Hemming said, “They’re signposts, early indicators of what Chinese wine can become.”

2017 Tiansai Sparkling Wine, Xinjiang (12% | 天塞起泡酒 2017,新疆)

The welcome drink was a sparkling wine from the Gobi Desert in Xinjiang – the first Chinese sparkling wine Hemming had tasted made in the traditional Champagne method.

Produced by Tiansai, a winery established in 2010, the wine is made from 75% Chardonnay and 25% Pinot Noir, and spent six years on the lees – a significant investment for any producer. On trend with zero dosage and no sugar added, the wine showed a savoury, dry finish. It was named best sparkling in its category at Wynn Signature Competition, as well as best for the Xinjiang region. Hemming noted that in a blind tasting, few would be able to pick it out from a lineup of good Champagnes.

What surprised Hemming even more was that producing sparkling wine requires exactly the right kind of fruit: early-picked, slightly under-ripe, with high acidity and neutral flavour, the opposite of what Chinese vineyards typically yield. Thanks to China’s landscape and growing conditions, the grapes tend to be super concentrated in flavour. These vineyards, surrounded by arid land with little greenery, rely heavily on irrigation and follow a very modern style of viticulture. Rather than planting by terroir, farms are laid out on flat plains, where different varietals, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir alongside Cabernet Sauvignon, Marselan, and others, are planted side by side. There is, as Hemming put it, “no obvious concept of terroir.”

The winemaker behind this sparkling is Lilian Carter, who also founded the winery. In addition to the 2017 Tiansai sparkling wine, she also produces a range of reds.

But the bigger question remains: would there be demand for a sparkling wine priced at S$120 (a direct converion from renminbi), made in a region not known for this style, and from a culture without the emotional attachment that typically drives premium pricing? Hemming raised this with his audience, noting that some producers market themselves like Rolls-Royce – pricing not to sell, but to position their wines as prestige products, creating a halo effect around the brand. Targeting the few, domestically, might just be enough. After all, with a population of 1.3 billion, China doesn’t need a large percentage of wine drinkers to sell an awful lot of wine.

In Wine with the Food of Asia, which Hemming co-authored, it’s suggested that sparkling wines are best paired with umami-rich ingredients like anchovies or dried shrimp, while dishes heavy on chilli are best avoided.

2022 Château Hesoute White Muscat, Xinjiang (13.5% | 合硕特酒庄麝香干白,新疆)

After the most expensive wine in the lineup, we moved on to the cheapest – a Muscat made by an agricultural university (中国农业大学), a training ground for budding winemakers. The wine is 100% Muscat, very dry, unoaked, with a strong fragrance and a well-balanced palate. “This is textbook Muscat, like absolutely on the button,” said Hemming. He added that the wine “would look comfortably at home” in a lineup of Alsace Muscats. It would have taken home the Muscat trophy, if there had been one. Instead, it claimed the award for Other Dry White.

Although Muscat isn’t a fashionable grape today, it had a moment in the early 2000s when it briefly became a Californian trend in Napa, often made off-dry and extremely aromatic.

Wines made at this university aren’t intended for commercial release, which explains the surprisingly low price: just S$17.50 a bottle.

Hemming referred to Wine with the Food of Asia and cited a similar example: Gewürztraminer paired with Sri Lankan fish curry (p.171), a match driven by the wine’s aromatic profile and the dish’s complex spice.

2022 Château Mihopé Viognier, Helan Mountain, Ningxia (14% | 美贺酒庄维欧,贺兰山, 宁夏)

The vineyard is nestled in a valley surrounded by mountains, drawing irrigation water from the nearby highlands. From this site comes a wine that took home the trophy in the Viognier category – a bold, ambitious expression of the variety aged in new oak.

Like Muscat, Viognier has a strong personality and can be divisive. It’s rich in stone fruit and tropical fruit flavours, which is opulent, aromatic, and not always to everyone’s taste. Very few regions outside the Rhône Valley produce Viognier well, though one Australian winery, Yalumba, is particularly known for doing it right. According to Hemming, this Chinese producer isn’t quite at that level yet, but the wine is still impressively executed, “It’s spot on,” said Hemming. “Very opulent, but not too cloying, not too candied.”

Aromatic grapes like Viognier are typically treated with a light hand when it comes to oak, to avoid masking their distinct character. This producer, however, took a calculated risk and ageing the wine in 40% new oak for six months, instead of the more common twelve. It turned out to be balance that allowed the powerful fruit to shine through without being overwhelming.

In Wine with the Food of Asia, Hemming picked Georges Vernay’s Le Pied de Samson, IGP Collines Rhodaniennes, a Viognier, to pair with Beijing duck (p.220). The wine’s stone fruit character complements the sweetness of the bean and hoisin sauces, while its ripe, unctuous texture matches the richness of the duck and the intensity of its fragrant spices.

2023 Petit Mont Baima Snow Mountain Degin Cuvée Prestige Chardonnay, Yunnan (14% |寸山白馬雪山得榮珍藏霞多麗,云南)

At an altitude of 2,763 metres above sea level, Petit Mont Baima’s vineyard sits high in the mountains of Yunnan, a region that Hemming describes as “the one to watch” in Chinese wine.

With dark soils, a low latitude close to the equator, and surprisingly moderate weather, Yunnan offers a unique climate, “Some of the greatest, most impressive and ambitious examples of Chinese wine I’ve tasted have come from Yunnan,” Hemming said, and this Chardonnay is no exception.

Made entirely in new oak, the wine was crafted under the guidance of Zhang Yanqi, who founded the winery in 2017 after studying under the late Denis Dubourdieu, the influential Bordeaux professor and winemaker behind several of France’s most iconic white wines. Dubourdieu’s legacy adds a significant level of prestige to the Chinese wine brand.

This Chardonnay, a trophy winner at the Wynn Signature Awards, reminded Hemming of the new wave of Australian Chardonnays, made in a fresher, high-acid style that’s crisp, elegant and far removed from the overly oaky expressions of the past. From a straight price conversion from Chinese yen, this bottle is priced at S$115.

In Wine with the Food of Asia, Hemming revealed that his favourite pairing for momo, the Nepalese dumplings, is still Chardonnay, especially when the filling features ginger and garlic and not dipping them into too much chilli sauce (p.142).

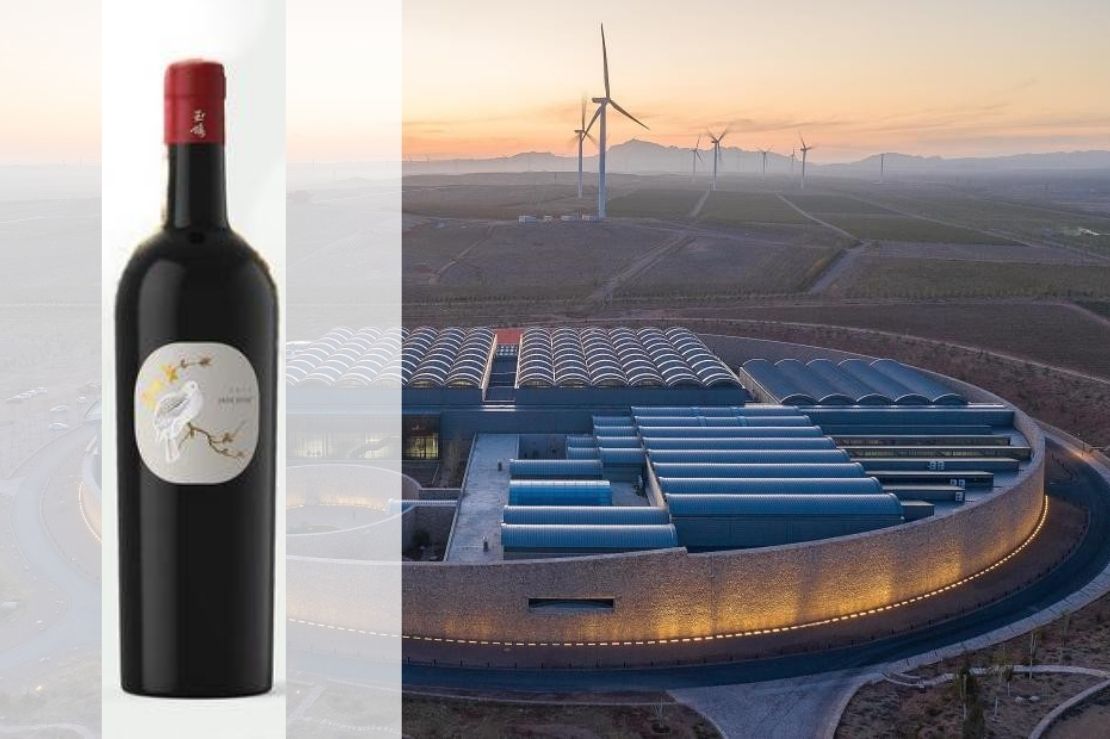

2021 Xige Estate Jade Dove Single Vineyard Cabernet Gernischt, Ninxia (14.5% | 西鸽酒庄玉鸽单一园蛇龙珠 2021, 宁夏)

Cabernet Gernischt is perhaps the first grape to be recognised as uniquely Chinese. It’s widely planted across the country and has become something of a national signature, drawing significant attention from both domestic and international wine circles. While the word “Gernischt” doesn’t exist in German or any other known language, it’s believed to be a misinterpretation of the German word gemischt, meaning “mixed.”

“Despite some debate still going on, Cabernet Gernischt is genetically Carmenère,” explained Richard Hemming MW. The grape, once prominent in Bordeaux, was thought to be lost to the Phylloxera epidemic, but it survived in China, having been brought into the country by Zhangyu Winery in 1892. While Carmenère has found a second home in Chile, it hasn’t quite achieved the same distinctive expression it has in China. “Cabernet Gernischt is something that China is potentially going to run with as a unique wine that nobody else can make,” Hemming remarked.

Jade Dove took home the trophy for Best Cabernet Gernischt. Like its genetic cousin Carmenère, the wine is defined by bold black fruit and a leafy, herbaceous character, both unmistakable hallmarks of the variety. Oak ageing lends additional structure and spice, rounding out a wine that is compelling for its taste. From a straight price conversion from Chinese yen, this bottle is priced at S$101.

What Hemming likes about the direction this winery is taking, is that they are leaning into the Chinese influence. They are branding themselves the same level as Penfolds, and even adopt their way of labelling their wines with bin numbering system. The winery produces 6 million bottles of wine each year, which demonstrates the capacity and breadth of the winery operation.

In Wine with the Food of Asia, Jade Dove was specifically highlighted as a representative example of Cabernet Gernischt, genetically identified as Carmenère, and recommended as a pairing for okonomiyaki, the Japanese savoury pancake layered with competing flavours. The wine’s distinctive green streak complements the cabbage and spring onions in the dish.

2018 Great Wall Chateau Sungod Syrah, Hebei (15.2% | 长城桑干酒庄西拉 2018, 河北)

Produced by China’s largest wine company, Great Wall, a subsidiary of the state-owned COFCO Group, this Syrah comes from Chateau Sungod in Hebei, a region just outside Beijing. Established in 1983, Great Wall has long played a key role in the country’s wine story, but this bottle feels like a modern expression of its ambitions.

At 15.2% ABV, the wine is big and bold, not unusual for Syrah, especially in the style of Hermitage. Still, Hemming questioned whether this particular wine was trying to carve out a distinct Chinese varietal identity, or simply emulate its Rhône counterpart. Either way, the wine is well-balanced as is.

“If you picked this up off the shelf and didn’t know what to expect,” Hemming said, “the first clue is the incredibly heavy bottle. The second is the alcohol level.”

That weight isn’t accidental. “These guys have a marketing department,” Hemming added wryly, noting that while heavy bottles are increasingly frowned upon in the fine wine world due to their carbon footprint, this particular one is clearly intended for the domestic market. Most of the back label is printed in Chinese, suggesting that sustainability concerns around shipping may not be as relevant here.

Retailing at S$194 after a direct conversion, this Syrah didn’t win a trophy at the Wynn Signature Awards but was highly commended and received several positive reviews.

In Wine with the Food of Asia, larb moo, often regarded as Laos’ national dish, is paired with a Syrah-dominant blend, chosen for its peppery character that mirrors the flavour of Thai basil used in the dish.

2012 Domaine Franco-Chinois Reserve Marselan, Hebei (13.5% |中法庄园珍藏马瑟兰 2012, 河北)

Domaine Franco-Chinois began as a joint venture between the French and Chinese governments, with its first vintage released in 2003. Today, it stands as one of the most respected producers in China, and its Marselan is a prime example of why this grape is gaining traction as China’s potential signature variety.

Though originally a French crossing of Cabernet Sauvignon and Grenache, Marselan was never widely planted in France. In China, however, it has flourished. It brings together the generous red fruit of Grenache and the structure and ageing potential of Cabernet, making it a well-suited variety for the country’s diverse and extreme growing conditions.

This 2012 vintage was aged in oak for 16 months and matured in bottle for 13 years before being presented at the masterclass. It was double-decanted, poured into a decanter, filtered for sediment, and returned to its original bottle for serving. The result was a wine that Hemming described as “conventional, mature, savoury, and full-bodied.”

One guest noted a smoky character, which Hemming attributed to the likely use of toasted oak, though this wasn’t specified on the label. With a price of around S$400 after direct conversion from renminbi, this was one of the most premium bottles in the lineup, and a reminder of how Chinese Marselan, despite its relatively short history, is already proving its age-worthiness and complexity.

In Wine with the Food of Asia, the Cabernet Sauvignon by Two Wolves is recommended alongside lamb kofta, the Persian-style version with green cardamom and fresh mint, for its bold fruit and succulent oak, both robust enough to stand up to the dish’s fragrant intensity. It’s a pairing profile that could just as likely suit a full-bodied, toasty oaked Marselan.

Across the seven wines, some themes emerged: high-altitude vineyards are producing some of China’s most exciting reds; aromatic whites like Muscat and Viognier show real potential; and Marselan is shaping up to be China’s flagship grape.

Hemming likened the tasting to a “Chinese treasure hunt.” Aside from the two better-known names, Ao Yun (owned by LVMH) and Long Dai (owned by Château Lafite), most of the producers featured remain largely unknown outside China. For Hemming, the real excitement lies in uncovering these lesser-known styles. “You won’t always strike gold,” he said, “but when you do, it’s truly exciting, because it feels like something new is being discovered.”

- T -