Every industry moves in cycles. The bar industry is no exception.

What feels different today is the number of pressures converging at once. Inflation continues to squeeze spending, food and beverage businesses are still repairing balance sheets battered by the Covid-19 years, tariffs and global logistics disruptions have pushed up the cost of spirits and ingredients, and consumer drinking habits have quietly but decisively changed. People are drinking and frequenting bars less, and asking harder questions about value and experience for their bucks.

In this climate, bars are closing, not just the experimental ones, but also establishments once buoyed by reputation and prestige. The era where a strong concept alone is fading but what remains durable, whether bars that are waging on or newly opened, the durability undeniably still relies one principle: the fundamentals.

That belief sits at the heart of the Monkey Shoulder Ultimate Bartender Championship (UBC), a competition that has steadily built credibility by focusing not on theatrical and creativity, but on the everyday skills that keep bars functioning no matter the conditions.

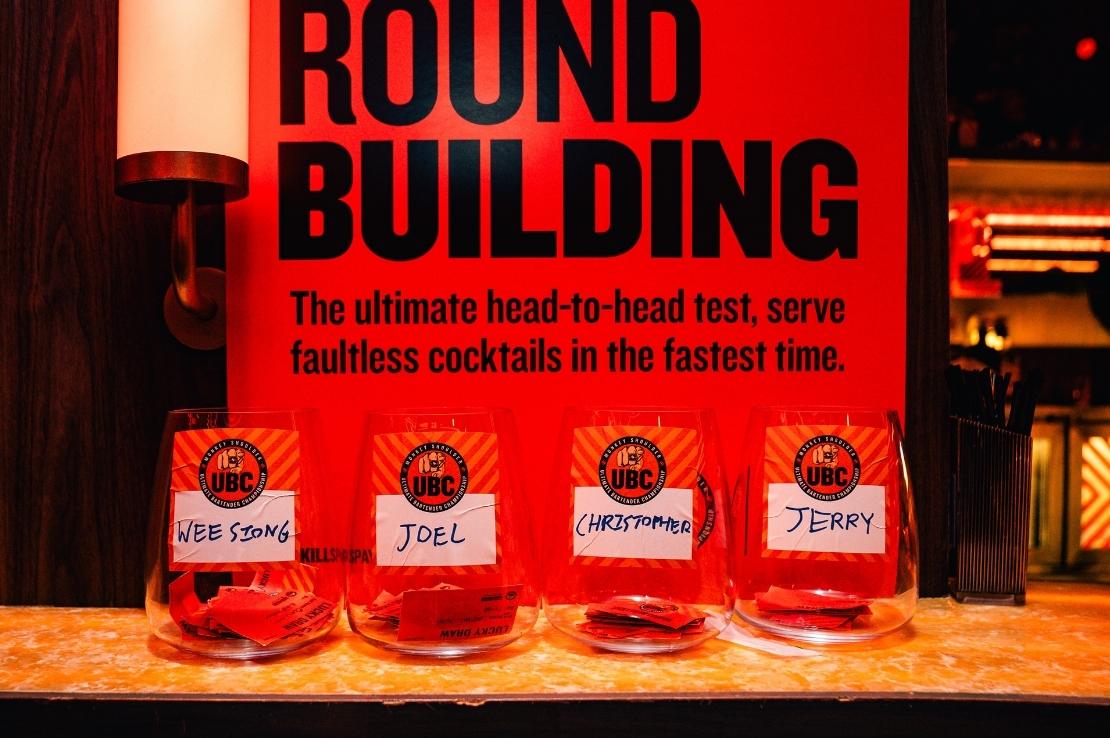

Contestants' name on glasses during the UBC 2025. [Photo source: Monkey Shoulder]

As Brendon Khoo, Monkey Shoulder’s Brand Ambassador for Southeast Asia, puts it, “A lot of competitions reward creativity, which is subjective. What we wanted was something that shows clearly where your skills actually are, not bias, not storytelling advantage, but merit.” This philosophy has never felt more relevant.

Challenges for Real Skills

The UBC was created as a deliberate counterpoint to traditional cocktail competitions. Instead of judging who can tell the most compelling origin story for a drink or deploy the most avant-garde technique, UBC strips bartending back to its essentials: Its tagline: “Skills That Pay Bills”, gives the competition its literal meaning.

“People try to run before they can walk,” Brendon explains. “UBC is about making sure you can walk properly first.” This year marked a significant milestone for the competition. For the first time since its inception, UBC expanded beyond national competitions into a regional final, bringing together winners from across Asia to compete on equal footing. The first regional final took place in Tokyo from 10th to 12th October 2025, alongside the DMC World DJ Championships.

UBC is intentionally structured to remove subjectivity. How? Each competitor must complete five core challenges, each worth an equal number of points, emphasising the idea that no single skill matters more than another.

1. Quiz

A fast-paced written test covering spirits knowledge, cocktail history, trends, and industry fundamentals.

2. Pouring Accuracy

Bartenders must pour precise liquid volumes using water, measured by weight. Margins for error are tight, and habits quickly reveal themselves.

3. Nosing (Sensory Test)

Ten spirits are presented blind. Competitors must identify both the category and brand, this tests memory, training, and palate discipline.

4. Table Service

A simulation of real-world service where bartenders must memorise orders (10 in the competition), navigate obstacles, serve the correct drinks to the correct guests simultaneously, and clear the table efficiently.

Table service round at the Ultimate Bartender Challenge. [Photo source: Monkey Shoulder]

5. Perfect Serve

Bartenders race against the clock to prepare a Monkey Shoulder Gold Rush cocktail, judged on speed, temperature, balance, hygiene, and accuracy.

Top-scoring bartenders advance to a final round-building challenge, where efficiency, composure, and consistency are tested under pressure. Most distinctively from other competitions, UBC uses referees, not judges. Scoring is transparent, standardised, and published, an approach Brendon describes as “meritocracy, not preference.”

A Regional First Where Asia Bars Come Together

The inaugural regional final brought together national champions from:

Indonesia: Yesaya Rotinsulu, Head Bartender of 8Souls Jazz Club, Jakarta

Malaysia: Ivon Soon, Head Bartender at Enso Izakaya & Bar, Hyatt Regency, Kuala Lumpur

Singapore: Wong Wee Siong, Head Bartender at The Lobby Bar, The Singapore EDITION

Taiwan: Okra Liu, Co-Founder of MUSOU Bar

Thailand: Saran Awiruttapanich, WYWS Cocktail Bar in Bangkok

The Philippines: David Abalayan, Bar Manager at No Entry Cocktail Club / Oto

Over 500 bartenders participated across Southeast Asia alone before national winners were selected. Emerging from that all that was Wong Wee Siong, Head Bartender of The Lobby Bar, The Singapore EDITION, who went on to claim the regional title for 2025.

The Story of a Chef Turned Bartender

Wee Siong’s story begins in the back of a family bakery. Growing up, he spent time helping his brother, a professional bakery chef where he learned the rhythms of dough, timing, repetition, and precision. That early exposure shaped his understanding of craft long before he studied hospitality.

He later pursued culinary training in Nilai University in Malaysia, specialising in culinary arts, and worked in hotel and restaurant kitchens. The kitchen, he recalls, was unforgiving but formative, “In the kitchen, timing is everything. It’s very strict. You follow instructions exactly and you don’t improvise.” But that discipline left an imprint even after he left the back-of-house years later, which he took to the bar today.

Kim: How did you first move from being a chef into bartending?

Wee Siong: I was introduced to bartending by a mentor. In college, I saw seniors doing flair bartending and it looked exciting. In flair bartending, you become the focus. I wanted to perform, to be on stage. My first bartending competition was with Monin. Before they developed into creative cocktail competition, they only had flair competition, and I really enjoyed it. I never expected to become a bartender. It took time to decide. Kitchen and bar are very different worlds. A mentor invited me to help open a bar, and that’s when I got into bartending.

Kim: What appealed to you about front-of-house work?

Wee Siong: After you prepared the food and if the guests enjoyed it, you don’t get to see it if you work in the kitchen. At the bar, you see guests’ reactions immediately. You talk to them, explain drinks, share stories, and they take pictures of your drink, that interaction is very enjoyable for me.

Wong Wee Siong (left) and Brendon Khoo (right) during the UBC 2025. [Photo: Kim Choong]

Kim: Did your chef background help you behind the bar? How are they different?

Wee Siong: Definitely. Chefs learn techniques, ingredients and discipline, which I can use in bartending. The difference is, timing is very important in the kitchen, and you are always rushed to finish a task. You also have to follow the book, the same task repeated and be fast. It’s very rigid in the kitchen. In bartending you can make the drinks based on your customers’ liking. If the guest want it a bit more sour, you can change that; or if they are stressed and want the drink more boozy, you can adjust the recipe too, so a lot more flexible and have room for creativity.

Kim: When did you transition into craft cocktails?

Wee Siong: After moving to Singapore, I worked as a bar back for some time. When I started At The Other Roof, I learned about flavour, ingredients, and balance in making cocktails. That’s when I really started crafting drinks.

Kim: Your first cocktail in Singapore was a Singapore Sling. What did it mean to you?

Wee Siong: The Singapore Sling is tropical and refreshing, and it’s a good starting drink for many people visiting Singapore. It’s the country’s national cocktail! Drinking it is part of the journey here. That’s why there were many orders for Singapore Sling every day during my time there.

Kim: You often talk about bringing joy through cocktails. What does that look like for you day-to-day?

Wee Siong: Every drink has a story. When you share that story, your personal experience and how the drink was created, guests feel something. That interaction alone creates joy. When people are happy at your bar, they come back again and again.

Kim: Is that how you train young bartenders?

Wee Siong: Yes. Hospitality comes first. Understand the guest’s mood, recommend properly, explain the drink. Make sure the guests feel that they are looked after.

Kim: What advice would you give new bartenders?

Wee Siong: Basics are very important. Don’t try to be a star on day one. Train hard, work hard, and learn properly. Always focus on service, then drinks techniques (shake, stir, balance) later. Imagine you are the guest and get served after guests who come later, you wouldn’t want that! We have a handbook (at The Lobby Bar) for any newcomers. It outlines outlet structure, table numbers, workflow, menu knowledge, serving standards, POS operation, guest etiquette... all to make sure that our guests enjoy their time with us.

Monkey Shoulder Gold Rush cocktail by Wee Siong at The Lobby Bar. [Photo: Kim Choong]

On Current Bar Scene and Guest Shifts

As the conversation widened to the broader industry, both Brendon and Wee Siong were candid about the current landscape of the bar industry. Labour shortages mean fewer hands behind the bar. Rising costs demand tighter control. Guests notice inconsistency more quickly when they are ordering fewer drinks. “In this climate,” Brendon says, “these are not optional skills. They are essential.” Accuracy ensures value for money. Speed improves turnover without sacrificing quality. Service discipline shapes the guest experience in subtle but powerful ways, especially when expectations are high and tolerance for mistakes is low.

Brendon questioned what guest shifts are really offering today. Are they just pop-ups where a visiting bar drops its menu into another venue for a night, or are they genuine collaborations built together with the host bar? For him, a guest shift should be worth the guest’s time and money, with the consumer clearly in mind because at the end of the day, they’re the ones filling seats and keeping bars alive.

Wee Siong hopes to see fewer routine guest shifts and more thoughtful ones. To him, the value lies in cultural exchange, learning how bartenders from different countries work with their ingredients, techniques, and traditions. A good guest shift isn’t just about showing faces, it’s about creating a shared experience that expose guests and bartenders to new perspectives which helps build real relationships along the way.

Stay tuned to Monkey Shoulder Ultimate Bartender Championship (UBC) Global Final 2026 through their website.

- T -